Written by

Australian Dog Lover

21:38:00

-

2

Comments

Overview of dog aggression and training methods

My name is Ryan Tate and I started my animal training career working with birds and marine mammals. I have trained Zebra finches for free flight and was one of the last people in the world to train leopard seals. Training animals at both ends of the size and temperament spectrum certainly gave me a lot of motivation to both understand and prevent aggression!

Nowadays my attention is primarily on dogs. My business is split between training and handling detector dogs, teaching animal studies, media work and private consultations in my area.

My aim is to be factual and avoid the emotional biases towards various techniques or terminology. As dog owners, trainers and humans, we all hold biases through our own experiences and perceptions. But... the reality is that there is no one technique that suits every dog or dog owner, and it is probably more influenced by the owners biases and experiences as opposed to the dog.

My name is Ryan Tate and I started my animal training career working with birds and marine mammals. I have trained Zebra finches for free flight and was one of the last people in the world to train leopard seals. Training animals at both ends of the size and temperament spectrum certainly gave me a lot of motivation to both understand and prevent aggression!

Nowadays my attention is primarily on dogs. My business is split between training and handling detector dogs, teaching animal studies, media work and private consultations in my area.

My aim is to be factual and avoid the emotional biases towards various techniques or terminology. As dog owners, trainers and humans, we all hold biases through our own experiences and perceptions. But... the reality is that there is no one technique that suits every dog or dog owner, and it is probably more influenced by the owners biases and experiences as opposed to the dog.

If you do own an aggressive dog please engage a dog trainer before attempting to put any of the concepts below into action.

When finding a dog trainer for assistance with aggression, I recommend considering only those with a formal qualification directly related to dog/animal training; and also own emotionally and behaviourally sound dogs they would willingly bring to your consultations. It is important to find a dog trainer you "gel" with, ask about their methods and see if it aligns with your own ethics.

The most common dog breeds I see in my area for aggression related consultations are Spaniels, Staffordshire terriers and herding breeds (Kelpies, Border Collies, Cattle Dogs).

When meeting a dog with aggression, I try to put their triggers for aggression into a category. Some of the categories may not scientifically be aggression, and many categories overlap (particularly fear) but most dog owners will identify the behaviour appearing as "aggressive".

What are the most common triggers for dog aggression?

The most common categories I see are related to:

1. Fear - towards dogs, people of certain phenotypes, vehicles, animals, children, groomers...

1. Fear - towards dogs, people of certain phenotypes, vehicles, animals, children, groomers...

2. Territory/Property - guarding the house, yard or vehicle.

3. Resource Guarding - toys, food, bones, people, beds.

4. Prey - towards cats, pocket pets, small dogs, children

5. Frustration - often seen in young dogs that were allowed to play with every dog they saw but now all of a sudden they are being restricted or not used to being on lead.

Some people might find it interesting that I haven't mentioned dominance or offensive aggression. It’s not that it doesn't exist, it does.

Some people might find it interesting that I haven't mentioned dominance or offensive aggression. It’s not that it doesn't exist, it does. However, in my experience the term dominance is too often used as an excuse for a dog that just hasn't been trained properly.

Dominance does exist in domestic and wild animals, but the way a dog displays dominance is a bit different to how a certain show with a "whisperer" might have you believe.

What are the most common categories of dog aggression?

I believe the most common reason these aggression triggers develop in the breeds I see are:

1. Lack of appropriate experiences in the critical development phase (< 16 weeks)

1. Lack of appropriate experiences in the critical development phase (< 16 weeks)

Often people assume a pup that has come from an unknown background must have been beaten because of the way it reacts towards men. Often we find out that this dog didn't get beaten by men, but rather it just never had any pleasant experiences with men in the first 16 weeks of its life.

The other side of the spectrum here is when people overdo it. For example they want their 8 week old puppy to love kids so they take it to a children's party for 4 hours. The pup gets overwhelmed and then develops a dislike for kids!

Prevention: it is all about the middle ground, exposing your puppy to "enough" without overwhelming it. Pleasant short encounters with people, dogs, and environments go a long way. Go to a good puppy pre-school with an instructor who has relevant qualifications, a well-socialised dog themselves and also promotes controlled interactions during puppy class.

2. Genetics and/or lack of understanding of a dog's genetics

If a dog and a bitch with high resource guarding are bred, the chances are the pups will show these tendencies too. Behaviour is genetic but we can certainly work on undesirable genetic traits if we know they are there in early development.

Many breeds were bred for hundreds of years to display certain aggressive behaviours such as guarding property or stock, or to be assertive when challenged or backed into a corner.

The other side of the spectrum here is when people overdo it. For example they want their 8 week old puppy to love kids so they take it to a children's party for 4 hours. The pup gets overwhelmed and then develops a dislike for kids!

Prevention: it is all about the middle ground, exposing your puppy to "enough" without overwhelming it. Pleasant short encounters with people, dogs, and environments go a long way. Go to a good puppy pre-school with an instructor who has relevant qualifications, a well-socialised dog themselves and also promotes controlled interactions during puppy class.

2. Genetics and/or lack of understanding of a dog's genetics

If a dog and a bitch with high resource guarding are bred, the chances are the pups will show these tendencies too. Behaviour is genetic but we can certainly work on undesirable genetic traits if we know they are there in early development.

Many breeds were bred for hundreds of years to display certain aggressive behaviours such as guarding property or stock, or to be assertive when challenged or backed into a corner.

Prevention: If you are buying a dog from a breeder, always INSIST on meeting the parents to see what their behaviour is like or if you're getting a rescue dog do your best to find out their breed(s) history so you can understand what types of stimuli might be a catalyst for aggression.

3. Single event learning

By that, I mean a highly stressful event, especially within the first year. The most common type of single event learning I see is usually caused at offleash dog parks, for example a young pup is taken to a dog park and rolled over or barked at by another larger or older dog.

By that, I mean a highly stressful event, especially within the first year. The most common type of single event learning I see is usually caused at offleash dog parks, for example a young pup is taken to a dog park and rolled over or barked at by another larger or older dog.

The young dog usually seems fine for a few months then seemingly out of the blue (often in adolescence) it starts to show aggression towards dogs, particularly dogs that look like the one that harassed them.

Prevention: Don't take a young dog to busy dog parks, do your best to prevent horrific experiences in the early stages of life and if your dog does have a seriously bad experience, see a dog trainer as soon as possible.

What are the different techniques used to treat aggression?

Now the tricky part! The methods and techniques that are used. I will explain the scientific terminology around the different techniques that are commonly used to treat aggression and the principles upon which they work.

#1. Counter conditioning

For example, every time the dog sees (or hears) what would usually trigger their aggressive behaviour, they experience a pleasant event such as a food treat, they will eventually form a pleasant association towards that thing that previously caused aggression, which in turn reduces the aggressive outbursts.

The emotions attached to the trigger have been changed and the emotion-driven behaviour also changes.

Sounds lovely doesn't it?

It is a highly effective form of treating aggression but often people struggle with some of the finer details that make all the difference. Understanding how the scientific principle was discovered will assist in applying it effectively in practice.

Counter conditioning has been around since the 1920s when researchers by the names of Mary Cover Jones and Ivan Pavlov were conducting revolutionary work. Both of their experiments and publications were of similar findings although Mary worked on children and Pavlov's theories were more widely accepted and were directly related to dogs so I'll focus on his methods.

Counter conditioning is considered to be a type of classical conditioning (also known as Pavlovian conditioning) which was described by Dr Pavlov in 1927. He worked out that when he presented food to a dog it would salivate. Then he started to ring a bell BEFORE presenting the food. At first the dogs behaviour did not change upon hearing the bell, but after repetition the dog started to INVOLUNTARILY salivate when it heard the bell, even before the food was presented!

Now if you are putting the pieces of the puzzle together you might start to understand that counter conditioning is trying to teach your dog that the previously scary stimulus (men, dogs, lawn mower etc.) is the bell! So your dog will eventually involuntarily enjoy the sight/sound of these previously scary triggers.

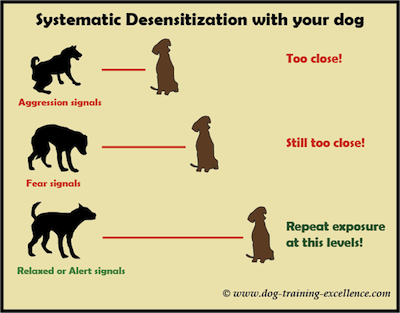

One of the aspects that is incredibly important when using this method is to ensure the dog is being given the food/toy/pleasant experience whilst below their "aggression threshold."

The difference from Pavlov's experiment was that the stimulus of a bell was a neutral stimulus (not scary).

Mary Cover Jones also noted that when conducting successful counter conditioning on children, the scary stimulus must be presented at a suitable distance as to not elicit fear. Throwing treats at a dog who has already lost the plot due to fear, is a bit like trying to teach someone how to swim whilst they are already drowning!

Another common mistake, particularly in the early stages of counter conditioning, is applying punishment/corrections in response to aggression from the dog. The aggressive behaviour has been displayed because the dog is over threshold, that's our fault, not the dog's! It's counter productive to use punishment during this process, particularly if the dog hasn't yet learnt a positive association.

So, what to do for success? You need to present the scary stimulus at a level where the dog will DEFINITELY observe it but not be triggered into aggression. This is also forms part of the desensitisation process.

What affects the intensity of the stimulus?

The distance from your dog, the volume, the duration of time your dog is exposed to it and the type of stimulus.

Additionally, physiological aspects can be contributing to aggression e.g. the dog's current cortisol levels, hunger and energy levels.

Counter conditioning can be difficult to implement if the dog has low food or toy drive, is highly frustrated, more motivated by their stimulus or in prey drive.

The reason being that if you don't have any bargaining tools or what the dog is focused on is more reinforcing than your "rewards", you can't make a positive association.

So the overall idea behind counter conditioning is that you are creating a new emotional association from something that used to make the dog scared and subsequently display aggressive behaviour; to something that leads to a pleasant experience and therefore makes them HAPPY!

The other methods that are used during training a dog with aggression form part of what is called operant conditioning.

#2. Operant Conditioning

B.F. Skinner is considered the "father" of operant conditioning and he described it in 1938. It works on two basic principles, if a behaviour is reinforced it is more likely to occur, if a behaviour is punished it is less likely to occur.

What is important to remember is that operant conditioning works on the principle of the dog having a choice of their behaviour, not emotion. What does this mean?

Well, you can't punish or reward emotion, only the behaviours the dog is choosing to do. You can punish or reward behaviours associated with emotion, but you may not change the emotional state.

For example if you hit a dog every time it growled at a child for picking up its toy the dog will probably stop growling, but that doesn't mean it is no longer feeling aggressive. What that dog might do is hide that growl and just bite the child when you're not looking.

For example if you hit a dog every time it growled at a child for picking up its toy the dog will probably stop growling, but that doesn't mean it is no longer feeling aggressive. What that dog might do is hide that growl and just bite the child when you're not looking.That doesn't mean operant conditioning should be overlooked for aggression, not at all. It is incredibly important and pivotal in training desirable behaviours that help deal with and prevent aggression such as basic obedience (heel, come, sit, stay). If your dog knows these basic commands (not just inside your home) you can prevent a lot of aggression.

Understanding operant conditioning also gives us an opportunity to ensure that the dog doesn't perceive aggressive behaviours as working for them or "reinforcing".

For example if a dog barks and lunges on lead because it wants to get to another dog, then allowing it to meet that dog whilst barking and lunging will reinforce that behaviour.

Taking it away from the dog when it starts barking and lunging will punish that behaviour.

On the flip side if a dog barks and lunges on lead because it is scared of a dog and does not want to meet it and the other dog moves away because of the barking and lunging then the barking and lunging is reinforced because the dog got what it wanted.

It might sound confusing but the aim of the game when using operant conditioning is to understand what the dog wants or does not want and utilise that to shape desirable behaviour.

For example, I know of a couple of cases of individual dogs having a lot of success killing and eating smaller animals, the sight of those animals even at distances of 50 metres or more was so arousing that they could not eat a treat...

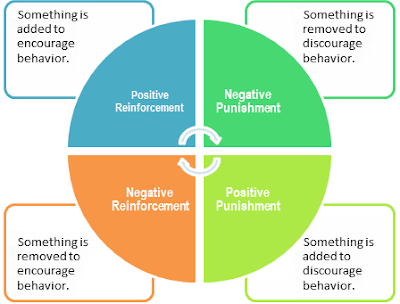

There are four types of operant conditioning:

1. Positive reinforcement: giving the dog a reward to strengthen behaviour you like: e.g. a treat or toy

2. Positive punishment: giving the dog something undesirable to weaken behaviour you do not like. Eg a tug on a leash, a whack on the butt.

3. Negative reinforcement: removing something the dog does not like to strengthen a desirable behaviour: e.g. removing pressure from the leash, removing a 'scary dog', letting a dog go free.

4. Negative punishment: removing something the dog does like to weaken an undesirable behaviour: e.g. removing food, toys, or social attention.

Important points to consider when working with aggression

- Rehearsal is reinforcement. The more the dog practices aggression the more likely they are to use it in the future. For example if you have a dog doing unwanted property guarding and you do five x 5 minute training sessions a day, rewarding the dog for calmly letting people walk past your house but then allow it to bark and practice property guarding aggression while you are at work, you will be unlikely to see the result you seek. In fact, the aggressive displays will probably worsen.

- Send a consistent message of what you want from your dog. I set a plan for my clients to follow for a minimum of 3 weeks before reviewing its effectiveness or changing any techniques.

- Give the dog "soak time" to allow things to be sorted in his brain. Too much new information can become confusing. Don't overload yourself or your dog.

- There may be times when a reduction in training is required, particularly if you have a young dog, a hyper dog or a dog that has had a particularly stressful experience. After a bad experience a couple of quiet days in a row can be more beneficial than "getting back on the horse" this is because after a highly stressful event the cortisol levels in the dog stay elevated for up to 48 hours, which means during this time the dog is much more prone to aggressive outbursts.

- Identify your dog's optimum genetic fulfilment vs. being calm. All of my dogs are high drive working dogs so there is a certain level of mental and physical stimulation they need in order to be calm. My spaniels need to search for things and my shepherds need to bite things! But I won't let them search and bite all day, they need to learn to chill out too!

- "Let them sort it out" is not a good idea, we don't need to place your dog or another dog at risk of physical or emotional injury to deal with aggression.

- Dogs are poor generalisers, what you teach them in one location or with one person does not automatically transfer to new locations or new people.

- Focus on what you want the dog to do, not what you don't want it to do.

There is no such thing as a quick fix with aggression, it takes time and consistency to make your dog happy and reliable in a variety of environments.

Take your time, plan ahead and don't give up on your dog.

About our writer

Ryan Tate is a highly experienced animal trainer (B.M.S, Cert. IV TAE, Cert. III Captive Animals, S.O.A. Dog Training). He has been professionally training animals for the last 13 years and recreationally since he was a child. He is a qualified Marine Biologist, Zookeeper, Dog Trainer and Assessor.

Ryan has experience training dogs, marine mammals, sharks, penguins, reptiles, birds and native Australian mammals. Ryan regularly appears on TV and radio for his expertise on training animals including a 2 part Series on the ABC Science Show “Catalyst: Making Dogs Happy”.

Ryan runs Tate Animal Training Enterprises with his wife Jennifer, also an experienced and accomplished trainer.

Excellent and extensive article, thanks Ryan!

ReplyDeleteGreat job Ryan, this is a superb overview. The one part I would disagree with is the idea that a trainer should have well-adjusted dog they feel comfortable bringing with them to client meetings. I adopted my 1.5 year old dog shortly before getting my certification and told the shelter I was going to be bring her out in public to the park and for my training course. Only after I tried taking her to those places did I go back and see that there was a code in her paperwork that signified that she was not supposed to be adopted out to the general public, only to shelter staff, due to behavior issues.

ReplyDeleteI am very comfortable with her around other dogs, and with people if I can set up the situation carefully, but it would not be fair to her or safe for my clients for me to bring her to client meetings.

I am confident that I could adopt a well bred puppy and provide them with excellent socialization and wind up with a well-adjusted dog, and I have helped many clients do so, but I am not going to do that simply to market my business or prove a point.

Additionally, I feel that my experience with my dog has helped me to learn the limits to which we can train away deep seated behavior issues and how we can still find ways to keep people safe, with management, controlling the environment, and tools such as muzzles. By the way I also know amazing trainers who *gasp* don't even own dogs!